Clothes cover, hide, and also shape the human body to a greater or lesser degree. The fashionable silhouette was always formed by the cultural and aesthetic norms of the day. Fashion would variously obscure or emphasise the body’s shape, even to the detriment of comfort and practicality. Clothing acquires semiotic significance, it speaks and informs, creating an artificial cultural physique endowed with its own language.

The installation of 18 outfits with examples of underwear presents fashion culture with a focus on shifting silhouettes over the course of two centuries, from the beginning of the 19th to the end of the 20th century. The selected exhibits illustrate the complex internal structure of clothing and underwear that strove to achieve the fashionable silhouette and a visually attractive adornment of the body. They can also be seen as artistic objects, further expanding our perception of clothes.

The human physique was also formed and impacted by the use of accessories and jewels. A separate thematic section presents the development of jewellery from the Middle Ages to artistic output of the early 21st century, showcasing the performative function of jewels based on their location and motion on the wearer’s body. More text next to the photos

Empire Style

Fashion in the Empire era (approx. 1790–1820) was ruled by simple, straight lines, inspired by the Enlightenment ideals of the free and individual development of the body and soul and a return to nature. It was also strongly influenced by the contemporary admiration of Ancient culture in connection with the excavations of Pompeii and Herculaneum. With a waistline raised to below the bust, the silhouette was formed by a comfortable corset with no emphasis of the waist. Slim women could accentuate their natural female form with short stays. The clothes supposedly belonged to Marie Tilleová’s great-great-grandmother Anna Krombholzová, whose husband was a lawyer for the Mladá Boleslav estate of Count Sporck. Marie Tilleová helped significantly expand the fashion collection at the Museum of Decorative Arts by donating or selling a large set of clothes of exceptional quality from her ancestors and a set of her own garments made by leading Prague couture houses of the interwar period.

Dress in late Empire style, c. 1820, Bohemia. Batiste, white embroidery

Biedermeier

The Biedermeier period (approx. 1820–1848) gradually transformed Empire fashion into a style that suited a harmonic and civil way of life. The ideal female form approached its natural proportions with an hourglass silhouette, featuring a slim waist, a form-fitting bodice, richly ruffled gigot sleeves, and a wide skirt suggestive of ample hips. The fashionable silhouette was achieved with short corsets and several underskirts of starched linen or of a fabric interwoven with horsehair. In the 1840s the ideal of beauty changed in the spirit of Romanticism; sleeves grew narrower, the fitted bodice was reinforced with boning, while the skirt expanded to such proportions that it needed to be supported by an underskirt with sewn-in hoops.

Walking dress in Biedermeier style, c. 1835, Bohemia. Taffeta

Style of Second Rococo

In this period, fashion developed the Romantic ideal into the playful, luxurious style of Second Rococo, with a fancy for laces, ribbons, and artificial flowers. The bodice remained tight, with a pointed extension at the waist, while sleeves were widened at the wrists. The skirt continued to gain in volume, forming a hemisphere in the 1850s and then flattening at the front and extending into a long train at the back in the subsequent decade. The ever-essential corset largely mirrored its Biedermeier predecessor, while a crinoline was required to support the skirt. This latter piece of clothing consisted of an expanding set of hoops made out of whalebone, withe, or later also from newly patented steel rods, connected vertically by twilled tape.

Summer dress in Second Rococo style, c. 1855, Bohemia. Batiste with printed pattern

Historicism, 1870–1890

The fashion of this era was marked by a historicising eclecticism that applied elements of Renaissance and Baroque clothing but struggled to achieve a distinctive silhouette. Its transformations over the course of 20 years mainly manifested themselves in the shape of the richly arranged skirt with a typically arched back section. This was achieved either with specific underwear in the form of pads, called tournures, or “honzíks” (“johnnies”) in Czech, with special lace-up underskirts, or by tying and tightening the lining of the rear section of the skirt. The upper body with a prominent bust and thin waist was shaped by a rigid corset.

Summer dress with bustle, c. 1885, Bohemia. Muslin batiste with printed stripe

Art Nouveau

The fashion trends of the 1890s abandoned the tournure completely, culminating in the arrival of Art Nouveau in the final years of the century. The Art Nouveau style stood in contrast to the preceding eras in its simplicity and natural feel. Although it accepted the biological proportions of the female body, it deployed a slight arching of the back at the waist, which emphasised the bust and the rear section of the hips but also deformed the body somewhat. This typical forward-leaning, “swan bill” curve was a kind of physical equivalent of the flowing line of Art Nouveau ornamentation. It was created using a stiff corset alongside a draped front on the bodice over a slender waist and a gathered or underlaid rear section on the skirt.

Afternoon dress with bolero, Art Nouveau, 1897–1900. Anna Watzek, Teplice (Teplitz), Bohemia. Wool fabric with silk pattern, velvet, silk lace, and embroidery with silk, beads, and glass stones

Late Art Nouveau

The final phase of the Art Nouveau fashion, which emanated from France starting in 1906, offered a Neoclassical style. It was based on reminiscences of the clothing of the French Directory and Empire periods of the turn of the eighteenth and nineteenth century, enriched with inspirations of an Oriental – especially Japanese – flavour, followed by Russian ballet. The silhouette featured a higher waistline with a short bodice consisting of folded, layered sections, with kimono sleeves and a straight skirt, often supplemented with a short train and tunic. This style did not emphasise the waist and did not require a corset, in line with contemporary efforts to reform women’s clothing. Nevertheless, corsets remained in use, though they provided more balanced support along the length of the chest and down to the hips.

Formal dress in late Art Nouveau style, c. 1912. Modes Robes Augusta Eisenbergerová, Prague. Silk satin, needle lace

The 1920s

In the aftermath of World War I, society created and embraced a wholly new lifestyle, which dramatically changed the lives of women especially. Advancements in emancipation, education, employment opportunities, sports, intense social activities, and modern dances necessitated a new way of dressing. Functional garments with short skirts, based on sports and boys’ fashion, were balanced out by sumptuous evening dresses replete with embroidery, fringes, and diverse decorations, intended for dancing to jazz rhythms. Women had discarded their corsets during the war, and modern underwear was exemplified by a breast-flattening brassiere, knickers, a suspender belt, and a slip or an envelope chemise (with buttoned crotch).

Afternoon dress from an outfit (dress, coat, hat), 1927. Rosenbaum Couture House, Prague. Silk georgette. Made for Marie Tilleová

The 1930s

The hallmark of 1930s fashion was a return to femininity and elegance, exemplified by lengthened skirts and designs. One of the popular patterns consisted of a flowing bias cut, which lightly enveloped a fashionably slim, flexible, athletic figure with natural female curves. The underwear that completed this figure included a shaped brassiere, an elastic suspender belt or latex corset that allowed the body to breathe, bell-bottom knickers, and a slip. Gradual changes appeared in the late 1930s in anticipation of war, with the inclusion of military elements such as broad shoulders, shorter skirts, and long trousers, while women’s curves were also emphasised with full busts, thin waists, and contoured hips.

Ball gown, 1936/1937. Hanna Podolská Couture House, Prague. Marocain and striped rep, covered with cotton tulle. Made for Hilda Podolská, daughter-in-law of Hanna (Hana) Podolská, for a ball held by the Czechoslovak Red Cross

Second Half of the 1940s

After World War II, fashion gradually regained its lost diversity. In spring 1947 Christian Dior presented his first collection in Paris, later dubbed the New Look. This novel fashion trend achieved its distinct hourglass shape with a corset that emphasised the bust and an underskirt that supported a wide skirt. The elegant look was complemented by high-heel shoes, gloves, a diminutive handbag, and a hat. Nylon stockings were all the rage. The demanding, high-consumption style was criticised as unethical considering the postwar scarcity of resources. All the same, it quickly spread throughout the world in the following years.

Outfit: jacket and skirt in “New Look” style, c. 1950. Prague, home-made. Cotton duvetyne, wool

The 1950s

A whole slew of fashionable silhouettes appeared over the course of the 1950s. Wide skirts prevailed again in the later part of the decade and the early 1960s. A youthful look became the preferred ideal, at the expense of strict elegance. The broad range of available materials, typical for the second half of the century, is readily apparent on contemporary underwear. The expansiveness of the skirt was formed by a polyamide net underskirt. Conical brassieres sharply accentuated the bust; they continued to be produced mostly from cotton and viscose, as were knickers. Summer fashions saw a great return to printed cotton fabrics internationally. Printed patterns imbued garments with diverse artistic inspirations, many of which were presented in the Czech pavilion at the 1958 World Expo in Brussels. The patterns were thus frequently dubbed “Brussels style”.

Summer dress, c. 1960, Mladá Boleslav, home-made. Cotton with printed pattern, Czech “Brussels style”

First Half of the 1960s

The early 1960s were dominated by a thin, straight silhouette. Dresses built on a sheath-like base with much less attention given to the bust. Suspender belts of various designs remained essential as body-forming underwear. Myriad dress types and patterns were used. Emphasis was placed on materials and colours. Vibrantly dyed curl pile was a popular choice. These soft materials allowed the clothes to be ruffled and gathered. Fashionable sleeve cuts were long and fitted or in 3/4 lengths supplemented with long-cuff gloves. The overall look was one of simple elegance.

Day dress, 1962, Prague, bespoke. Woollen curl pile

Second Half of the 1960s

The second half of the decade brought a number of major changes to fashion. Miniskirts were finally acknowledged in 1965. Long, slim legs became the body’s signature visual. The ideal trendy type of childlike appearance was devoid of all female attributes like prominent breasts or hips. Garters, shaping bras, and stiletto heels lost their appeal and were replaced by flat bodices, tights, and low-heel shoes. Popular choices included shirt dresses or dresses that widened slightly towards the hem, made of cotton or synthetic materials, occasionally with lurex fibres. The trend was to reveal and relax the body. Fabric patterns were inspired by op art and pop art or by colourful psychedelic designs.

Mini dress and hat, 1968. Part of a multi-purpose outfit: trousers, blouse, swimsuit, shoes, hat, and fashion jewellery ÚBOK (Institute of Home and Dress Culture), Prague, designed by Květa Škamlová (born 1930). Fabric by TIBA Dvůr Králové nad Labem, national enterprise. Printed cotton satin

First Half of the 1970s

The end of the 1960s and the whole 1970s were characterised by a slew of new clothing styles based on contemporary ideological currents, especially the hippies movement or punk. Instead of creating a new silhouette, the culminating tendencies of the previous decade were developed. Fashion ceased to respect social mores, and a new philosophy bloomed: the freedom to wear whatever you want, whenever and wherever you want to. The common imperative was for the body to appear natural. The ideal figure was slim. Young women stopped wearing bras. Trousers, which had previously been worn by women only for leisure activities, were the new deal in fashion. One of the most favourite outfits consisted of wide-leg trousers and a form-fitting blouse or sweater.

Button-down blouse, 1st half of 1970s. Former Yugoslavia, branded “Bačkaprodukt”. Printed polyester

Second Half of the 1970s

Fashion trends in the second half of the twentieth century were closely related to developments in the production of synthetic fibres. In the early 1970s, the consumption of chemical and natural fabrics was almost balanced. But public attention slowly began to prefer natural fibres. The growing popularity of natural materials was based on their pleasing qualities, but, more importantly, it was also an expression of humanity’s efforts to compensate for the increasingly technologised environment and budding ecological problems. One example of this development was the romantically styled cotton summer dress. The silhouette remained the same as in the beginning of the decade. A new type of unlined brassiere made of synthetic elastic materials conformed to the natural contours of the body.

Summer dress, 1977, ÚBOK (Institute of Home and Dress Culture), Prague, presumably designed by Květa Škamlová (born 1930). Lace by Vamberk Production Cooperative. Printed cotton, cotton bobbin lace

First Half of the 1980s

The fashion symbol of the 1980s was a silhouette with markedly broad shoulders shaped by massive padding and a renewed emphasis of the bust. The new clothing style drew from the philosophy of the young generation born in Western Europe of the 1960s, founded on the ideal of hard work and high expenditures. This worldview – accompanied by the opinion that a career-building person must be properly dressed – was also an expression of women’s emancipation efforts. The ladies’ version of this trend lent itself to a fitted suit with exaggerated shoulders and a short, narrow skirt or trousers. Another variant was to wear a dress with emphasised shoulders and ruffled sleeves, with a balloon skirt sometimes made of shiny synthetic materials.

Summer dress with wide shoulders, 1984. Styl, Módní závody Praha (Style, Prague Fashion Works), designed by Zdena Bauerová (born 1930). Synthetic fabric

Second Half of the 1980s

V 80. letech se vedle dominantní linie X se širokými rameny a útlým pasem prosadila také linie A, rozšiřující se ke spodnímu okraji, a linie Y se širokými rameny zužující se dolů. Diskuse o délce sukní přestaly být aktuální. Nejběžnější se ustálila kolem kolen. V oděvech se uplatnily asymetrické kombinace, netopýří rukávy, aplikace různého charakteru. Stále se zvyšovala obliba úpletů ze syntetických i přírodních materiálů. Prádlo se nosilo jednoduché s promyšlenými konstrukčními prvky nebo zdobnější vhodné pod elegantní oděv. Objevily se i elastické korzety tvarující postavu do měkkých oblých boků a prsou spíše měkce zploštělých.

Letní šaty s aplikacemi, kolem r. 1985, Daniely – Daniela Flejšarová, Praha, viskózová pletenina, hedvábné aplikace

Second Half of the 1990s

The minimalistic fashion of the 1990s retained its day-time austerity. The silhouette of the flawless young body remained indistinct, but evening dresses were ushering in a new type of underwear – push-up bras with elevated cleavage and shape-up knickers that formed the buttocks and flattened the belly. Workplaces required maximum conformity, ideally a dark suit, which became the unisex uniform. But this strict approach was dropped for evening and social attire. Clothing could be romantic, intensely feminine, and also highly revealing. Women were as likely to wear satin miniskirts with form-fitting tops as they were floral-patterned dresses. A “shockingly” vibrant pink was the popular colour of the time.

Summer dress, 1997. Designed by Martina Nevařilová (born 1965), branded “Navarila”. Acrylic knitwear, printed viscose, polyamide

Gothic Era – The Karlštejn Treasure

The discovery of a trove of Gothic items made of precious metals, the so-called Karlštejn Treasure (see also Hall Microcosms), testifies to the breadth of jewel types crafted in the period, ranging from fully sculpted objects intended to be viewed from all directions to flat ornaments designed to adhere to their wearer’s body with their reverse side hidden. The first type is represented in the treasure by the pomander – a spherical openwork case with decorative metalworking. This pendant container would hold solid perfumes, such as ambergris. Jewels could thus be perceived by multiple senses. Flat jewels are represented by a buckle and finial, which would have been mounted on a girdle. The buckle secured the jewel to the body, while the finial hung down like a plumb line.

Karlštejn Treasure (selection of jewels and adornments), late 14th century, Europe (Bohemia?)

Articulated Jewels of the Renaissance

Girdles, neck-chains, and rings enclose the body, binding it both literally and symbolically. They are worn on places where the body changes volume, where it tapers or expands. Renaissance chains often encircled their wearer multiple times. They could also be used to hang other elements of jewellery, such as a medallion or a watch. The wearer would thus display these items for all to admire, while being able to hold them, inspect them, and manipulate them. Watches were one of the articulated jewels of the Renaissance. Sections of a watch could be opened or tilted, with the clockwork mechanism ticking inside. The interior of the device could sometimes be viewed through a layer of transparent material, mainly rock crystal. Even the smallest of jewels – the ring – offered a degree of convertibility. A popular type of Renaissance ring was made of several hoops that could be folded apart but not fully detached.

Foldable sphere ring, c. 1600, Central Europe. Gold (combination of techniques)

Baroque Sophistication

Jewellery sets allow the same combination of materials, shapes, and colours to appear on – or dangle from – various parts of the body and clothes. Baroque jewellery sets use richly shaped and ornamented metal lattices, set with stones on the obverse. The mass of the stones was usually refined by a lapidary, who would cut the surface into multiple flat planes, called facets. These allow the gem to shine in certain conditions of lighting and perspective while staying translucent in others. The sophistication of the Baroque jewel is augmented by sculpted and painted figural scenes, such on a watch case, where they provide a counterbalance to the dial. Hidden messages can also be found in jewels without moving parts. For example, scenes on the exterior of a ring could be continued on the interior side, which was hidden when worn.

Set: earrings and pendant, 4th quarter of 18th century, France (?). Gold, silver, emeralds, sapphires, garnets, pearls

The Classical Order – Sets in Empire Style

Extensive jewellery sets from the early nineteenth century offered a palette of jewels. A lady would choose either a complete set or select pieces depending on circumstances. The adornment emphasised the upper parts of her body, mainly her head and nape. The motives of the jewels, such as an antiquising cameo or a glass mosaic, were applied in various semantic combinations according to the occasion. In rare cases, individual parts of a jewel could be separated or repurposed. The cameos on the tiara of the exhibited malachite set are fixed with gold screws, which allowed the jewel to be easily converted without any goldsmithing skills. The frequency of manipulation with the central section of the tiara is evidenced by its level of damage compared to the surrounding elements.

Set: tiara, necklace, and pair of bracelets, pre 1806. Franz Kobek (company; ascribed), Vienna. Gold, malachite

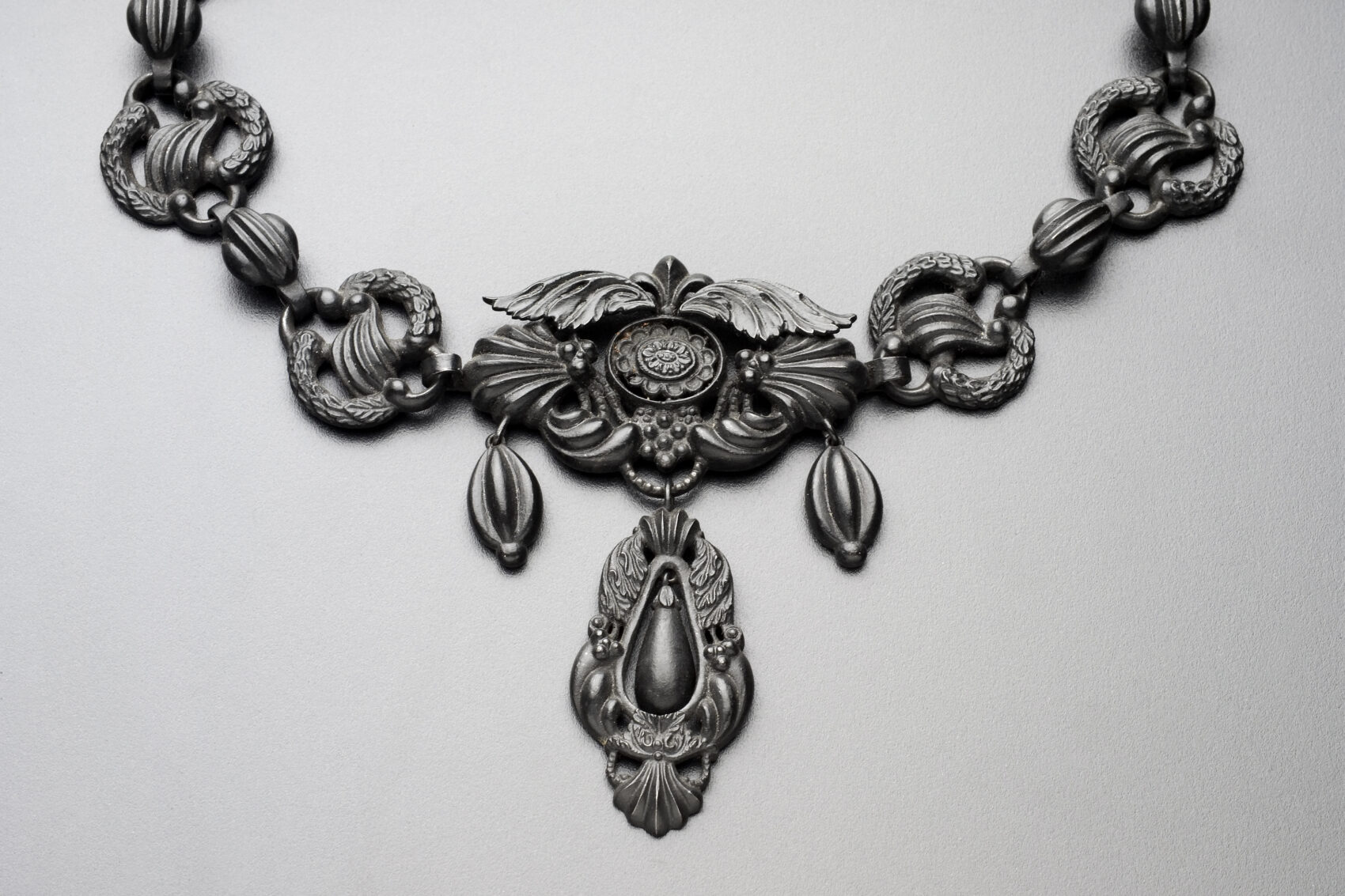

Inspirations from Nature and Architecture

The movement of the wearer supports the illusion of natural and fantastical worlds within the jewel. Jewellery in the nineteenth and early twentieth century assumed some of the qualities of living matter, mostly in their shape, colour, or surface. This lifelike appeal was also evoked by the manner in which the jewels were set – the decorative centrepieces were often mounted with the use of springs, individual components were suspended on eyelets or projected on pins. Jewels thus resembled the swaying of plants in the wind, the flitting of insects, or the fidgeting of birds. The wearer’s body became a landscape with shifting light, where the same plant can be observed at once in bloom and in the maturity and decay of its fruit, as illustrated by a plethora of materials and finishing techniques. The “topography” of the body is also superbly complemented by jewels that follow the precepts of architecture.

Necklace, c. 1830. Hořovice (Horzowitz) Foundries – Komárov, Bohemia. Cast iron

Moderna

Marie Křivánková (1883–1936), design. Bracelet, after 1910. Made by Pavel Vávra, Prague. Gold, Bohemian garnets, mother of pearl

New Dialogue of Jewel and Physique in the 20th Century

In the second half of the twentieth century, jewels instigated sensations of the physique both through the effects of items made of mutable and immutable materials and through a concept that discounted material objects completely. In the first variant, the tangible object was shaped in correlation with human anatomy, either before – in the artist’s studio – or after it was attached to its wearer. Both wearer and worn are mutually deformed in this relationship. Jewels accentuate the connections between body parts that are commonly obscured. Yet they can either remain remote from the body or enter into it. In the second case, free of any physical artefacts, the character of a jewel is imbued into a staged event and shared experience, similarly to how a traditional jewel generates a sense of personality and commonality.

Josef Symon (1932–2021). Ring, 1970s. Silver, partly gilt