Chambers with curiosities and art, known as Kunstkammers, served as treasuries where the encyclopaedic collections of European royal courts were preserved in the early modern age. They were remarkable compilations that wove together natural sciences and philosophy with the world of art. Their purpose was not just to amass a diverse plethora of artworks, valuables, and natural materials, but to build up an organic creative complex of knowledge. One of the greatest cabinets of curiosities was held by Emperor Rudolf II (1552–1612) in Prague at the turn of the 16th and 17th century. It was a grandiose creative workshop and scientific laboratory, in which the emperor figured as an educated and respected partner to numerous artists, scholars, and scientists from around Europe.

As universal founts of wisdom, cabinets of curiosities were to unveil the secrets of the microcosm and macrocosm. They were generally organised in three main sections: naturalia – everything found in nature; artificialia – the products of human artifice or natural objects modified by man; scientifica – items of a technical or scientific character. These categories were sometimes supplemented with mirabilia, a grouping of peculiar and miraculous phenomena. Overall, their structure can be divided into two ideational concepts – amazing artefacts resulting from the marriage of human spirit and divine power in nature and objects that would allow mankind to understand and control nature.

The collections were organised on the esoteric principle of the unity of the universe. Kunstkammers were an open edifice, an endless labyrinth where everything was interconnected. Minute objects were stored in cabinets, which contained many a curiosity and unexpected surprise. Despite the chaotic appearance, visitors’ motion and perception allowed them to uncover the inner logic of these universal encyclopaedias of knowledge.

More text next to the photos

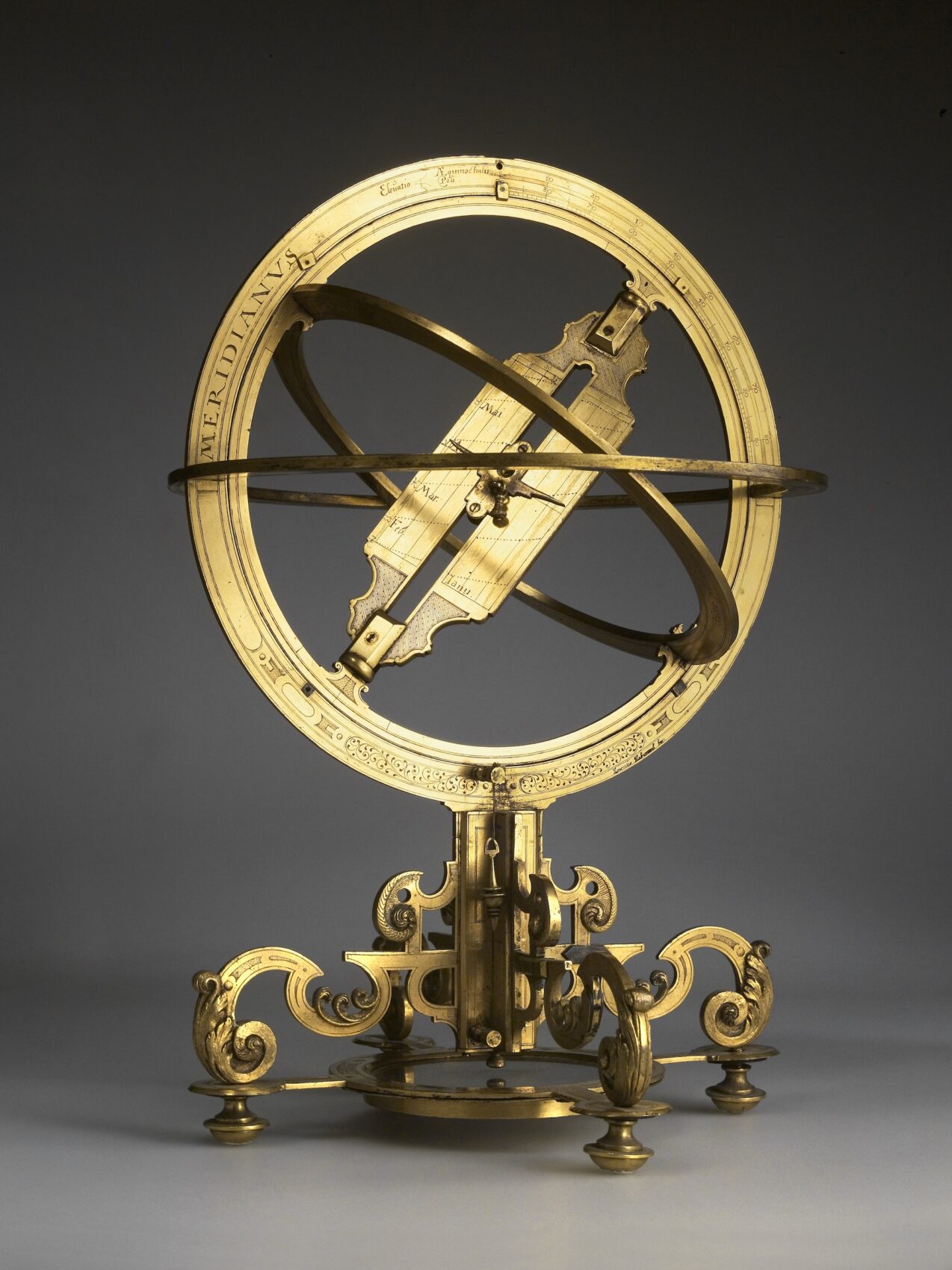

In the Kunstkammer’s encyclopaedic structure, objects of a technical nature enjoyed a high status. Mechanical instruments were greatly admired as ingenious creations that penetrated the mysteries of nature created by the divine “Mechanic” and facilitated its domination. The height of this combination of science and the arts was manifested by astronomical devices, clocks and various mechanical contrivances – movable automata. The Kunstkammer of Rudolf II housed works made by outstanding specialists in the field – the Imperial clockmaker Jost Bürgi and the court instrument maker Erasmus Habermel. Modern scientific instruments were constructed there under the guidance of the court mathematician Johannes Kepler and the Danish astronomer, astrologist and alchemist Tycho Brahe, and it was owing to them that Prague under Rudolf II emerged at the lead of mathematical and astronomical research.

Equinoctial ring sundial with stand, c. 1600, Erasmus Habermel (c. 1538–1606), Prague. Brass, engraved and gilded

In the late 17th century, marquetry created by the pre-eminent Parisian ébéniste (cabinet-maker) André-Charles Boulle that combined organic and anorganic materials was a greatly admired technique of decoration used for luxurious furniture. Boulle work was soon to be successfully imitated beyond the borders of France. A highly valued variant of this technique is represented by pieces made in the regions of southern Germany and the Danubian area, where furniture closely akin in style was produced particularly at the courts of Vienna and Munich. The cabinet from the Augustinian Abbey in Brno, with gemstones inlaid in its marquetry decoration, is one of the most distinctive Boulle-type creations of this circle.

Cabinet à la Boulle marquetry, c. 1710, Vienna. Tortoiseshell, pewter, brass; gemstones: lapis lazuli, jasper, agate; palisander and ebony marquetry; linden wood, carved and gilded; bronze, cast, chased, and gilded. Loaned from the property of the Augustinian Abbey of St. Thomas in Staré Brno

In the 17th century, the Free City of Eger (nowadays Cheb) was famed for the manufacture of luxurious cabinets and caskets decorated with so-called Eger relief marquetry. Associated with this technique that combined classic intarsia with glued-on carved reliefs is Adam Eck (1604–1664), a member of a large family of wood-carvers from Nuremberg. This cabinet used to be also considered one of the unique accomplishments of Eck’s workshop; however, more recent research aligns it with the circle of works by the so-called Master of Reliefs with Ornamental Backgrounds. The iconographically intricate decoration of the cabinet comprises the biblical parable of the Prodigal Son, the legend of Diana and Actaeon from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the personification of the Four Elements and Four Continents, the allegory of the Liberal Arts, and grotesque motifs à la commedia dell’arte. The subjects derived from earlier print series represent not only moral examples with literary allusions, but in their totality provide a picture of the whole world in a succinct metaphor.

Cabinet with Eger relief marquetry, c. 1650. Cheb (Eger). Pillar base from the late 19th century. Eger relief marquetry of various woods; ebonized pear wood (veneers, slats); pine wood (construction components)

Tabernacles, containers for reserving liturgical vessels holding the Eucharist, were typically placed in the centre of an altar. Its structural treatment in the form of a small temple – a miniature of a cathedral cupola – had numerous precursors in Italian Renaissance art. This form was later adopted for some central cabinets that constituted focal pieces of Kunstkammern. In the context of natural philosophy of the time, such cabinets became “holy shrines” of universal wisdom – pansophism. The inscription in its interior provides detailed information about its maker. It was made in 1745 by the Capuchin friar Frà Francesco da Belluno (Carlo Dolabella aka Francesco Dalla Dia). He was the Order’s cabinet-maker and wood-carver, a pupil of the prominent Baroque sculptor and wood-carver Andrea Brustolon. The tabernacle was completed, perhaps after an alteration in the commission, by the Belluno cabinet-maker Giuseppe Banna with his assistants in 1748.

Tabernacle in the shape of a polygonal temple, 1745. Frà Francesco da Belluno (Francesco Dalla Dia 1711–1788). Belluno, Veneto, workshop of the Convent of the Capuchin Friars Minor. Poplar heartwood (veneer); pear wood (carved relief sections); coniferous wood (construction parts) and other woods

Reverse paintings on glass (verre églomisé) were luxurious artefacts represented in many princely Kunstkammern, including the Rudolfine cabinet of curiosities. Venus with Cupid, rendered by Hans Jakob Sprüngli, refers to typical attributes of art collecting. The naked Venus is surrounded by various objects symbolizing the accoutrements of a cabinet of curiosities and Rudolfine art, whether these are goldsmiths’ works (a vase with flowers on a chest, a jug in the foreground), a lute and a mandoline, or an antique bust. The author of this masterpiece was from Zurich but he also travelled for comissions to Nuremberg and Prague, and was a sought-after proponent of the Mannerist art of reverse painting on glass.

Venus with Cupid, c. 1610. Hans Jakob Sprüngli (1559–1637), Zurich. Glass cut and polished on both sides, reverse painting in combined technique (Amalierung): engraved gold foil, backed with vellum, oil temperas and translucent paints, pewter foil; ebony frame (from 1868)

The Loštice goblets were noteworthy for their unusually coarse, blister-like surface texture, due to which these vessels were believed to have protective power against furuncle diseases. The advancement of medicine, mineralogy and also curiosity collecting incited interest in another type of ceramic called terra sigillata (i.e. seal-stamped). This ware was made from ancient times from a special, extremely fine clay to which healers attributed exceptional medicinal properties. The porous body of the vessels was to ensure the release of curative mineral substances into the beverage. The production of terra sigillata was initiated by Emperor Rudolf II; later, Jablonné v Podještědí (Gabel) on the Lords Berka of Dubá estate became the main deposit of the healing clay. Like the Loštice goblets, this medicinal pottery was also held in princely Kunstkammern, including the Rudolfine cabinet of curiosities.

Loštice goblet, second half of 15th century, Loštice (Loschitz), northern Moravia. Stoneware, graphite-treated, with coarse texture and traces of salt glaze

The work of Caspar Lehmann has drawn the attention of all admirers of the art of glassmaking for centuries. Period sources designated him as the founder of glass engraving and, although it is known that he was not the only one in this field, his creations are today works unparallelled in the world. Lehmann was employed at the court of Rudolf II from 1588, later the emperor appointed him “court gem-cutter” (1601). In 1606–1608, he was active in Dresden at the court of the Elector of Saxony. After returning to Prague, he was granted the Imperial privilege to practice glass engraving. The portrait of Christian II, considered one of Lehmann’s finest masterpieces, could have most likely been made during the artist’s sojourn in Dresden, or possibly during the Elector’s visit to Prague in 1602. The Lehmann Beaker, showing central allegorical figures of Power, Nobility and Generosity, was commissioned by Wolf Sigmund von Losestein († 1624), who was a military advisor and Imperial councillor to Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor, and afterwards court marshall to other Habsburg emperors. The beaker’s exceptionality rests not only on its superb craftsmanship but also its being the world’s first known signed and dated work to have been executed in the glass engraving technique.

Wedding beaker with the coats-of-arms of Wolf Sigmund von Losenstein and Susana von Rogendorf, and three allegorical figures, 1605. Caspar Lehmann (1563/64–1622), Prague. After an engraving by Jan Sadeler the Elder (1550–1600). Glass, hand-blown and engraved

The passionate penchant for gemstones to which the occult sciences attributed specific powers, spurred Rudolf II to seek out these precious minerals on Bohemian territory and to build a specialized workshop for gemstone cutting and engraving. Already in the late 1580s, Ottavio Miseroni, who came from a distinguished family of Milan gem-cutters, settled in Prague. His son Dionysio and grandson Ferdinand Eusebio extended the tradition of Rudolfine gem-cutting well into the late 17th century. Ottavio mastered a variety of techniques of engraving vessels and cameos, mostly in rock crystal, agates, jaspers, topases and heliotropes. This jasper bowl is shaped as a shell, partly devoured by the mouth of a monster, whose head adorns the top of the shell.

Footed bowl, early 17th century, (foot 19th century). Ottavio Miseroni (1567–1624), Prague. Jasper, heliotrope (foot)

Renaissance art collections were intended to demonstrate the relationship between natural and artistic forms, the transitions between the miracles of nature and human creations. The inventory of Rudolf’s Kunstkammer therefore began with naturalia records: the horn of the mythical unicorn, zoological preparations, and objects made of rhinoceros horn, ivory and tortoiseshell. Goldsmith’s works, such as coconut goblets and nautilus shells (artefacts made of shells of sea animals), presented the artistic treatment of organic materials, blending human genius with the divine forces of nature. Hence, the Kunstkammer offered a telling picture of the world in its diversity and breadth, according to the principle of natural philosophy and magic, i.e. that “everything is everywhere” (omnia ubique). In this open structure, every object can be related to another based on analogy; for instance, stones as “the bones of Earth” can be aligned with the bones of animate beings, ivory, but also rare woods (ebony).

Nautilus, before 1609. The Netherlands. Nautilus shell; silver, embossed and gilded

Allegorical representations of the elements, the senses and seasons of the year played an important role in the subject matter of small-sized sculpture of the High Baroque period. These objects are executed mostly in porcelain and ivory. Besides Augsburg in southern Germany, the center of ivory carving in those days was Dresden, where outstanding exponents of this specialized cabinet art worked, among them the court sculptor and carver Balthasar Permoser.

Aeolus, Keeper of the Winds, early 18th century. Dresden, Balthasar Permoser (1651–1732)? Carved ivory

The Kunstkammern cabinets of curiosities housed not only serious objects but also grotesque and jocular items. This wine glass, equipped with a silver windmill, had an entertaining function – the windmill set into motion by blowing into the tube measured the time it took the drinker to empty the glass.

Trick goblet, c. 1600, Augsburg. Green glass, free-blown; gilt silver

A unique illustration of glassmaking mastery were table adornments, such as the Venetian sweetmeat dish. It ranks with the most valuable artworks that the museum acquired through the generous donation of its co-founder and patron Vojtěch Lanna (1836–1909). In his day, his arts-and-crafts collections were among the world’s most outstanding art holdings and attested to his profound connoisseurship.

Boat-shaped vessel (table adornment), second half of 16th century, Venice. Colourless and blue glass, hot-shaped, cold painting

Florentine mosaic (commesso di pietre dure) was avidly admired by Emperor Rudolf II. He therefore summoned to Prague specialists directly from Florence – namely, Cosimo Castrucci and his son from his first marriage, Giovanni. Mosaics produced by the Castrucci workshop are exceptional for their composition alone consisting of minerals of Bohemian origin, with jaspers and agates being particularly noteworthy for their rich colour palette and patterns. The landscape and vedute became a specific genre of this production. The view of Prague Castle is one of the best known commessi from the workshop of Giovanni Castrucci. This view was most likely based on a veduta by Johann Willenberg from 1601, or possibly the view of Prague published by Aegidius Sadeler in 1606.

View of Prague Castle and Lesser Town, post 1601 (frame later addition). Giovanni Castrucci (documented in Prague 1598–1615), workshop, Prague. Commesso di pietre dure: agates, jaspers and other gemstones

The unique collection of secular Gothic silverware from a goldsmith’s workshop of the second half of the 14th century belonged to a member of the Luxembourg Court. It was discovered in the late 19th century by masons during restoration work at Karlštejn Castle (Karlstein). Besides a sizeable corpus of clothing adornments, jewellery and fasteners, it contains several pieces of tableware for formal dining, with ornamentation indicative of the court milieu of Emperor Charles IV. The engraved royal crown on the handle and the medallion with a relief female bust on the inside bottom of the bowl, which is reminiscent of the portrait busts produced in the masonry workshop of Peter Parler for the triforium of St Vitus Cathedral in Prague, places the bowl within the context of the Bohemian royal court.

Bowl, 1360–1380, Bohemia. Silver, cast, embossed, and gilded. Donated 1995 by Jiří Waldes

The Renaissance era saw a strong revival of the Pythagorean and Neo-Platonic conceptions of the universal harmony of the cosmos, based on geometric and numerical ratios. There was an evolvement of teachings on Platonic solids, regular polyhedrons, that were regarded from ancient times as the basis of all the elements. The most perfect of these solids was to be the dodecahedron that represented all existence and thus formed the essence of the entire Universe. These teachings were also endorsed by astronomers and astrologists at the court of Rudolf II, including Johannes Kepler, who attempted to apply the harmony of Platonic polyhedrons to the solar system model.

Polyhedron, late 16th century, Germany (probably Dresden). Coaxial set of skeleton dodecahedrons, lathe-turned and carved ivory, inside with a central full solid with protruding spikes, lathe-turned stand

Kunstkammers were not only treasure troves of accumulated wisdom, but also played the role of creative workshops and laboratories. The wealth of collections provided a stimulus for scientific exploration and magical experiments, and was also exploited by physicians and natural scientists, as well as astrologists and alchemists. Occult sciences in particular often contributed to the development of learning and new discoveries. The alchemical experiments performed by Johannes Kunckel (c. 1630–1703), who worked at the courts in Saxony and Brandenburg, led – instead of the intended manufacture of gold – to the discovery of gold ruby glass that became a luxurious article of the Baroque era.

Beaker with cover in gilded mount, c. 1700. Southern Germany, Augsburg – mount, marked “J.B.” Engraved ruby glass, gilded mount. Purchased 1891 in Vienna

Even better known is the story of the German alchemist Johann Friedrich Böttger (1682–1719), who – in his quest for the Philosopher’s Stone during his employ in the services of the Elector of Saxony – was the first in Europe to discover “white gold” – porcelain.

Vase from a fireplace set of Count Heinrich von Brühl, c. 1730, Meissen, Höroldt period. Porcelain painted in overglaze colours

The aquamanile – a water vessel – was used for hand-washing during Mass but also secular dining. It usually had the shape of a horse, lion or mythical animals. The aquamanile unearthed near Košíře (now part of Prague) was purchased in 1821 by Johann Franz II Neuberg von Neuberg (1769–1830), a member of a family that built over several generations and amassed in Prague one of the most outstanding art collections. After the death of his grandson Johann Eduard in 1892, UPM acquired 440 art objects from this collection (notably carvings in ivory, boxwood and mother-of-pearl).

Aquamanile in the shape of a horse, first half of 13th century, Lower Saxony or Bohemia. Bronze, lost-wax cast

Art collecting in the Renaissance drew on the traditions of church treasuries of the Middle Ages and, through classical literature, also reflected the legendary collections of Antiquity. Ancient artefacts held an important place in Kunstkammers, attesting to the evolution of creative skill and linking the past with that period. It was therefore not only the artistic quality, oddity or magical power of these objects, but also their antiquity that were much-valued criteria in those collections. This kind of bowl, called cyphus in Latin, is strongly suggestive of the ancient type of vessels with horizontally opposed handles, which served for drinking water-diluted wine. The cup is decorated with enamelled birds in an interwoven frame formed of eight quatrefoils (stork, eagle, goose, vulture, heron, swan, mythical phoenix, and onokrotal – a type of pelican). These decorative bird motifs, originally from the Far East, were disseminated via Venice to Italy and France, and became part of the ornamental repertoire of the International Gothic style.

Footed bowl, c. 1350, Bohemia. Silver, embossed, engraved, pierced, and gilded; translucent enamel